The story so far

The story so far

What makes the Durham First Folio so interesting and significant? How did it get to Durham in the first place? And what are we doing to conserve the book? Read on to learn more about the story so far and our exciting plans for the coming year.

The Durham First Folio is unlike any other Folio in the world. From its birth out of single sheets of paper and individual pieces of type to its present condition, the history of our book is unique. Here, we explain what makes it so special and what we are doing to preserve it.

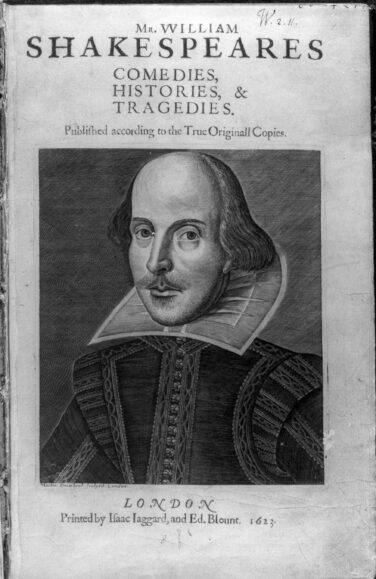

For many scholars, the First Folio is the closest they can get to the words William Shakespeare composed, even though at the time of publication – 1623 – he had been dead seven years. The First Folio was the outcome of a long-running project by his friends and admirers to establish a fitting memorial to him.

It was the first book ever printed in a large format only to contain dramatic works and it emerged in a relatively new market for printed plays. Because of the cost to produce the Folio, the book was not cheap (about £150 in today’s money) and the first owners were among the wealthiest and most politically important people in society.

These days, the First Folio is not particularly rare. Out of an estimated 750 copies that were printed, 235 are known to exist. That includes two copies that were only recently rediscovered in privately owned libraries and the copy owned by Durham University. So why do we celebrate this book and its author?

Without the First Folio, we would have lost 18 of the 36 plays contained within it. For example, that means we would not have the text for The Tempest or Macbeth. Shakespeare has had a lasting impact on the English language as well. We use phrases from these plays perhaps on a daily basis.

The Folio has also become a cultural icon and is symbolic of the impact and adoration of Shakespeare’s works. It has become an object of fascination for collectors and admirers, leading to high-profile auctions, high sale prices, and the kind of emotional veneration often reserved for religious artefacts.

The Durham First Folio also has a personal significance for people in Northeast England. The theft and recovery of the book had a major impact on how it was perceived. Its return is a communal source of pride and serves as a local connection to national heritage.

Some time before 1632, when the Second Folio was published, a copy of the First Folio was acquired by John Cosin. As a young man, Cosin was ambitious and attending dramatic performances was a popular past-time for the royal court. As Shakespeare had already found, theatre-goers were also increasingly interested in reading the plays as well as watching them. It is therefore possible that Cosin bought a copy to educate himself.

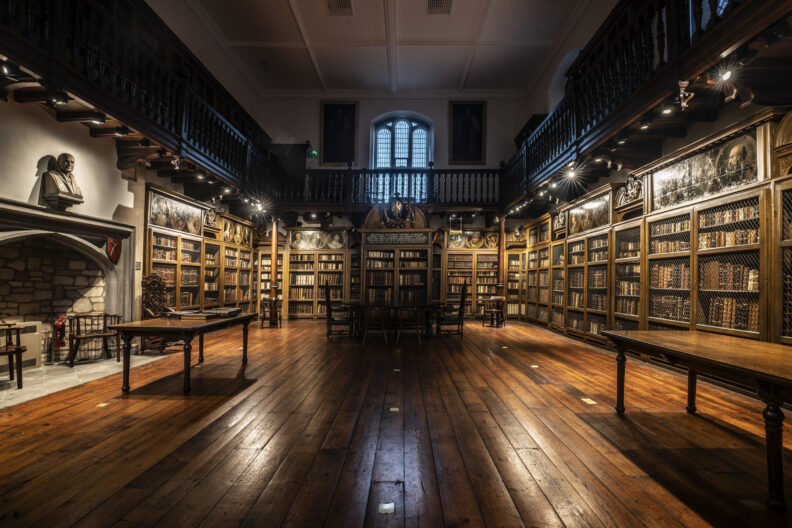

When Cosin was forced into exile in the early 1640s, because he was a royalist and High Church Anglican, he left the Folio along with his other books at Peterhouse, a university college, in Cambridge. After his return to England in 1660, when Cosin was made Bishop of Durham, his library was taken north. By 1670, the Folio had made its way to the shelves of the newly opened library on Palace Green. Cosin intended this library to be publicly accessible, making the Durham First Folio one of the few copies that has been in a public institution for most of its existence.

Although originally Cosin’s copy of the First Folio is likely to have been in a fairly plain brown calf leather binding, as was the style for book bindings in the early 17th century, in the mid-19th century it was rebound in pebble-grained brown goatskin with metal clasps on the fore edge, and the leaf edges were trimmed and gilded. Despite still being quite understated compared to other bindings that appeared on First Folios elsewhere, the act of rebinding the book may indicate a growing recognition of its cultural significance.

In December 1998, the First Folio, two medieval manuscripts and four other printed books were stolen while on display in Cosin’s Library. For a decade, there was no news of the missing books and Durham University had to accept that, after being part of Cosin’s Library for nearly 400 years, the First Folio was lost.

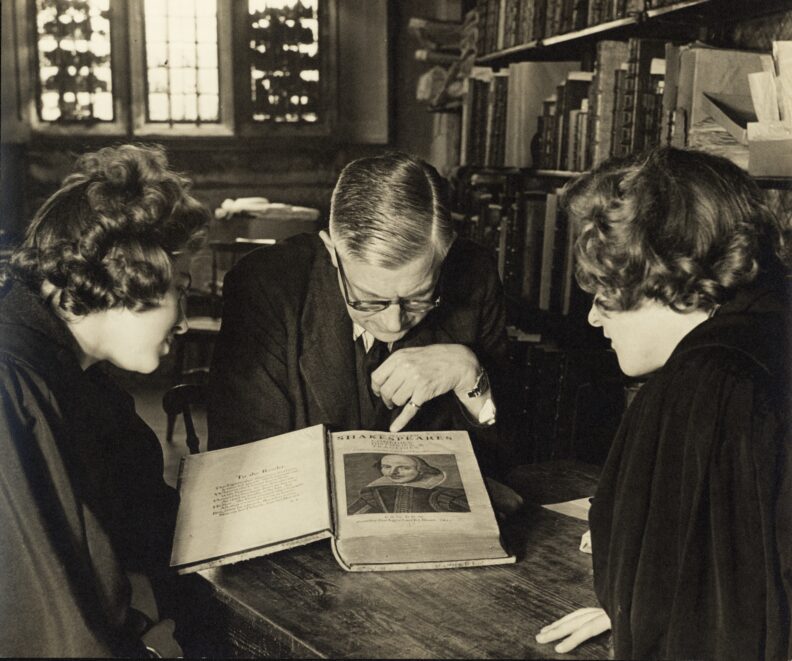

The story of the Folio’s recovery is an extraordinary one. In 2008, a badly damaged book was brought to the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C. The book was presented to experts as a newly discovered copy that needed authentication for sale. Staff at the Folger, home to the world’s largest collection of the printed works on William Shakespeare including 82 copies of the First Folio, quickly recognised the possibility that this book was in fact Durham’s missing copy.

Shakespeare scholar and First Folio expert Anthony James West was brought in to establish the book’s true origins. West outlined a number of tests of identity: no single test would be sufficient to prove this was the Durham copy, but passing all tests would leave little doubt that this book could be anything else. Failing any one of these tests would cast serious doubt on the possibility that this copy once belonged to Durham.

West compared the damaged copy with notes about Durham’s copy that had been submitted for a census of known First Folios in 1901, along with later bibliographic descriptions and photographs. Each test of identity was passed and a court of law ruled that the damaged Folio was indeed Durham’s copy. After a decade, it was returned to its rightful home on Palace Green.

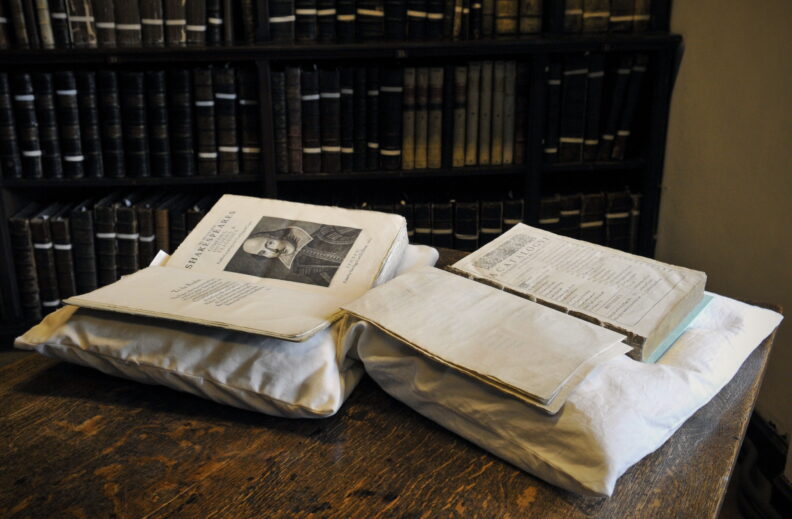

At some point after its theft in 1998, the Durham First Folio was badly vandalised in what appeared to be a deliberate attempt to remove its most obvious identifying features.

The 1843 pebble-grained goatskin binding had been torn away and discarded in its entirety, as had several of the first and last pages of text on which ownership marks and other identifiable notes had been written. When it was returned to Durham, it had no boards or leather to protect the paper textblock, several pages beyond those that had been discarded were torn out of the book, and the sewing, which holds the textblock together – was fragile and vulnerable to further damage.

On its return to Durham in 2010, the Folio was briefly exhibited in celebration. Since then, it has been housed in a custom-made enclosure in a secure and environmentally controlled room in Palace Green Library. Considered too fragile for regular use in teaching, it has only been brought out for inspection by conservators.

The 400th-anniversary of the printing of the First Folio has presented the opportunity for us to review the Folio’s condition and decide how to return it to its use within the academic and wider community.

Seeing a book as iconic as the Shakespeare First Folio in a vandalised state can elicit quite an emotional reaction, and at first the proper course of action seems clear: rebind the book, returning its functionality, beauty, and inherent dignity. However, the Folio’s current condition tells a dramatic story and rebinding would be an irreversible process of breaking down the First Folio to its constituent parts and replacing damaged materials with new ones to form a beautiful but entirely modern book. Physical links to the book’s history would be lost forever.

Before deciding on a course of action that would so change the nature of the book, we needed to weigh the options to ensure any decisions we make would not negatively impact the book’s use or appreciation by either the academic or wider community.

To achieve this, we spoke with a variety of people to find out what exactly they consider to be so special about the Durham First Folio, and how they would hope to see it used in their community going forward. Stakeholders included Shakespeare academics, Royal Shakespeare Company theatre directors, students in a variety of subjects from both Durham and other institutions across the country, and University staff, many of whom are Durham residents.

After gathering this more nuanced understanding of the significance of Durham’s First Folio, our conservators convened an advisory panel of experts in the field of book conservation to recommended how best to conserve the Folio in a way that respects and preserves the significance assigned to this book by its community: by recognising the importance of its current condition and reflecting its individual past while also allowing access and exhibition.

We are now working on a programme of action based on the committee’s recommendations. You can follow along on progress on our blog.