Studying Historic Bindings to Create a 17th Century Facsimile, Part I

‘What is past is prologue’

As part of our project with Shakespeare’s First Folio, there has been some exciting work going on in the Conservation Studio at Palace Green Library.

Currently in progress are three Shakespeare’s First Folio models, modern facsimiles rebound to replicate the 17th century characteristics and techniques that were likely to have been used when the Durham First Folio was first bound in 1623.

Many historic books are subject to changes in binding over time, with the age of the binding often not matching the age of the printed book.

The Durham First Folio’s original 17th century binding was removed and rebound in the 19th century by Charles Tuckett. The Tuckett binding was radically different both aesthetically and structurally to the original binding, however, rebinding in this way was very common practice at the time, in keeping with ever evolving binding styles.

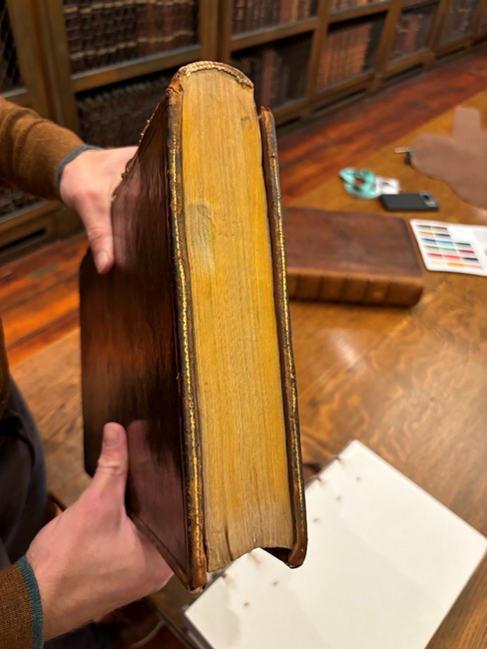

By looking at surviving bindings from the early 17th century in Cosin’s Library, we were able to discern the nature of materials needed and techniques to craft the book.

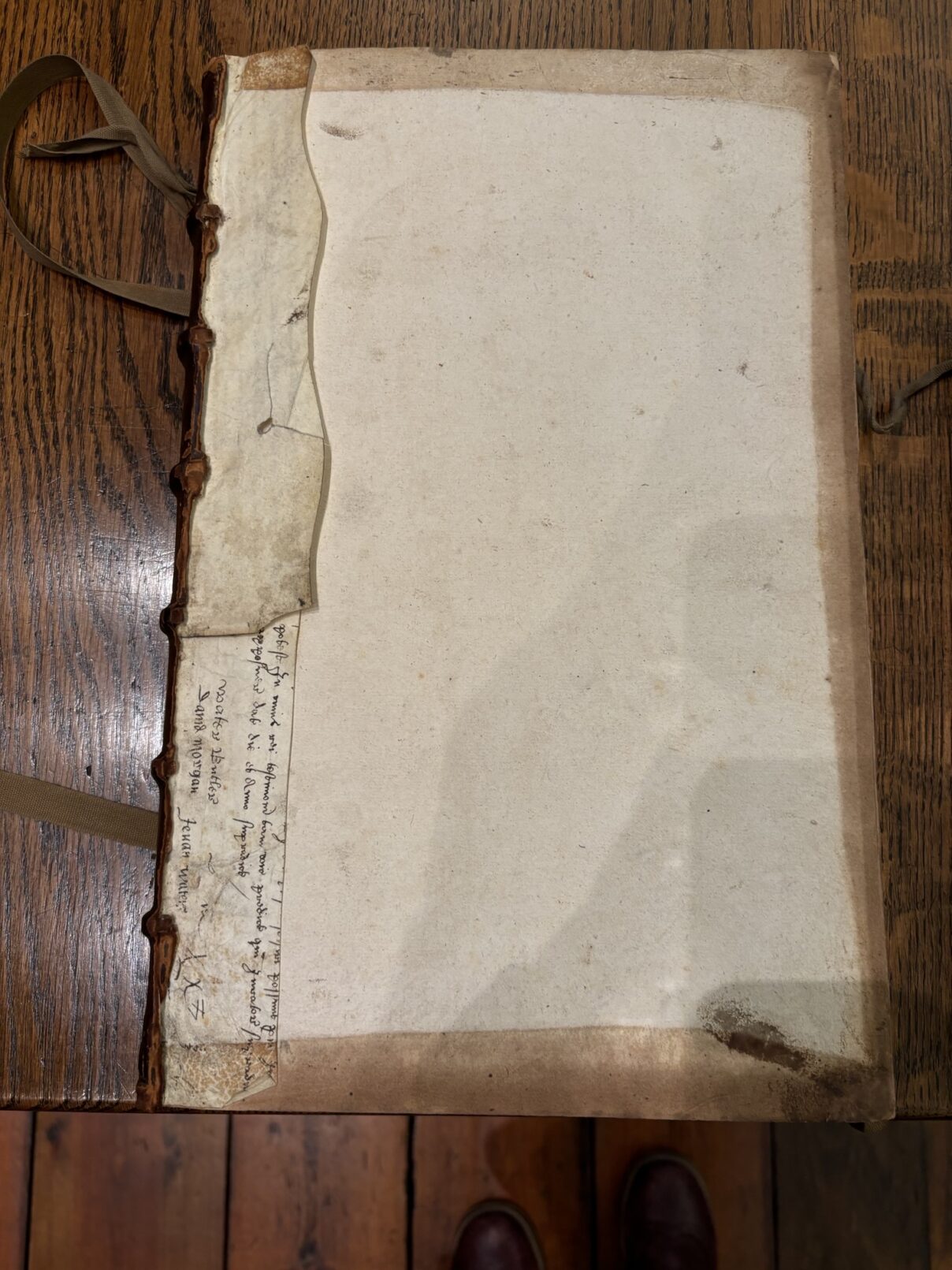

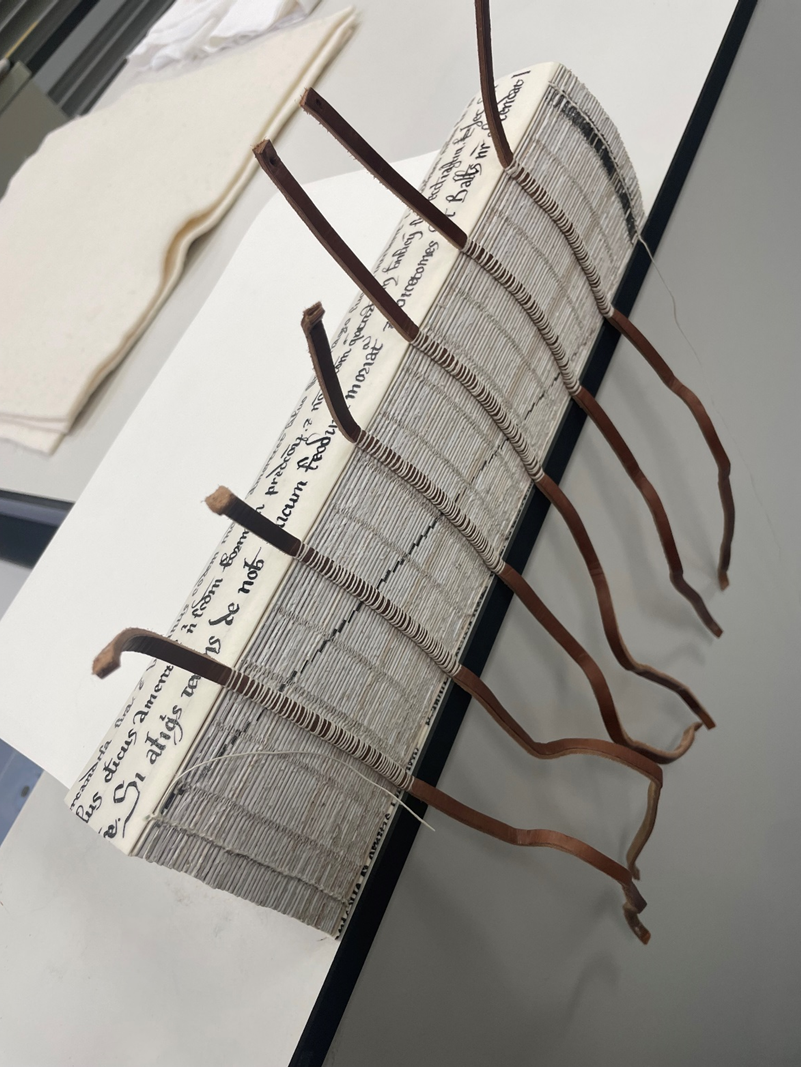

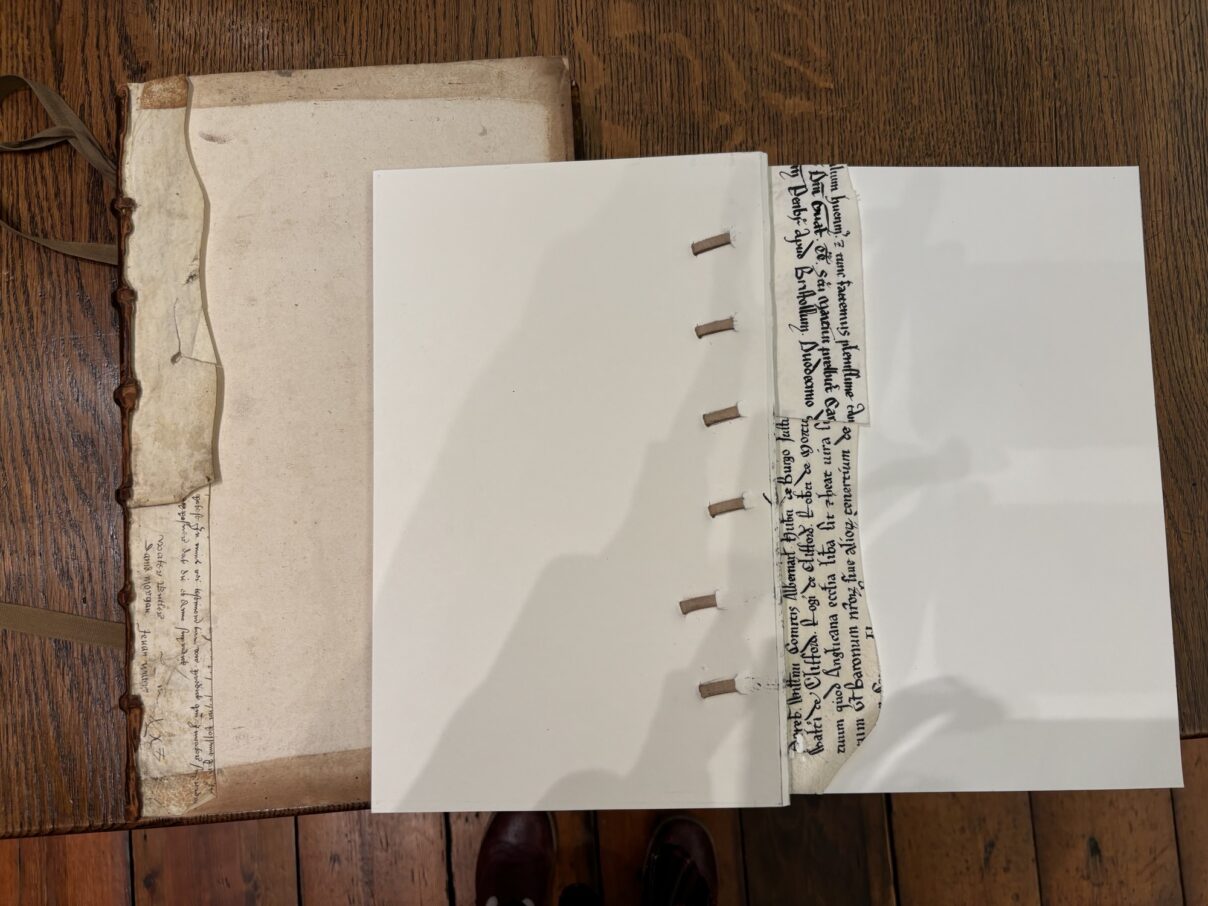

Some distinct features we found were laminated leather sewing supports (an average of 6 on books around the First Folio’s size), scraps of waste manuscript sheet sewn over the endpapers, head, tail and foredges painted yellow, and plain brown calf leather with black speckling used to cover the boards and the spine.

Beginning the Binding

We purchased the British Library’s 400th anniversary facsimile editions of Shakespeare’s First Folio for use of the high quality, printed text block, which we carefully disbound.

Books are composed of folded sheets which are collated together into gatherings. The book is sewn by passing a needle and thread through the fold of the gatherings and over supports that help hold the gatherings together. We made our sewing supports by laminating calfskin together, then set these up on a piece of equipment called a sewing frame.

There were 56 gatherings to sew, plus two end leaves, making this a rather lengthy process; but upon finishing we were met with a fully sewn text block looking characteristically 17th century.

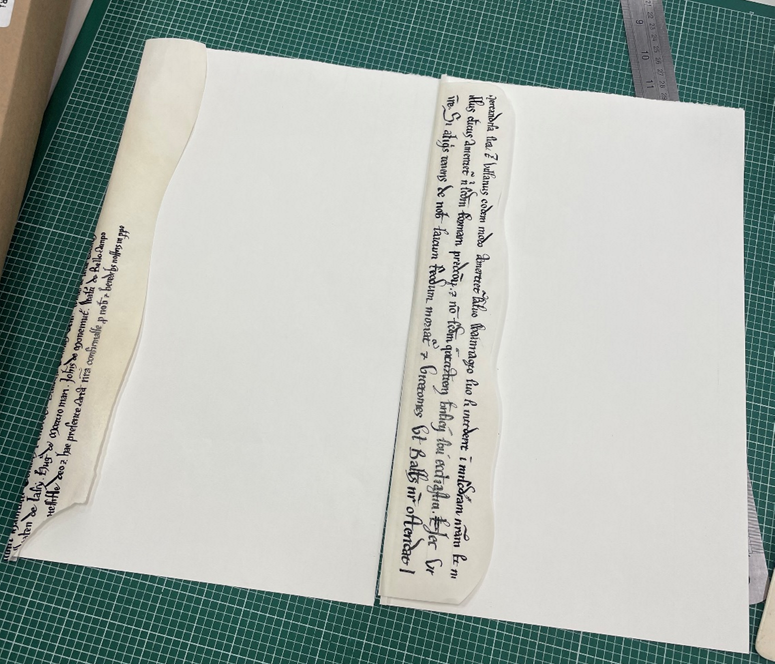

Waste material from discarded manuscripts was commonly incorporated into bindings in the 17th century, as a historical form of recycling. We recreated this for our models in keeping with all the historical evidence we saw in Cosin’s Library by adding manuscript waste to the endpaper structure (the blank leaves you find at the front and back of books even today).

Our incredibly artistically talented conservator, Joanne, did some beautiful calligraphy onto parchment that we were able to sew onto the endpapers to represent this component of the binding.

Intern’s Reflection

As the current Lendrum Intern in Book Conservation at Palace Green Library, this was my first experience of sewing a book of this size. I certainly underestimated how long it would take to sew, but after sewing about 15 gatherings, the process started to flow, and became a little faster.

The sewing thread certainly didn’t ‘bite’ into the supports quite like it does with the linen cord sewing supports we usually use, so I had to ensure I regularly checked the tension of my sewing and rectified where appropriate.

This was also my first time sewing onto leather sewing supports. I found it a lot trickier to ensure that my sewing had even tension throughout, as the sewing thread doesn’t ‘bite into’ the stiff leather quite like it does with the linen cord sewing supports we usually use. I learnt to use a needle vice to exert tension through the sewing thread as it was pulled over the sewing support, to prevent areas of uneven tension.

I really enjoyed sewing this model and am excited to progress onto the next steps. It has been a wonderful learning experience.

What Next?

The next steps are to move onto the finishing touches of the binding: attaching the boards, painting the edges, sewing the end bands, covering with leather, and tooling. Be sure to check back soon for another instalment which will further update on the progress of this project!

The 17th century facsimiles, once complete, will be available for visitor handling in the near future.

We also intend to make First Folio models in a 19th century style binding so visitors can see, feel, and observe how the materiality and design of bindings has changed over the centuries.