A Book’s Reputation

Reputation is an idle and most false imposition; oft got without merit, and lost without deserving.

Othello, Act II Scene 4

The first time I saw a Shakespeare First Folio, I was a high school student on a field trip in Washington D.C. visiting the Folger Shakespeare Library. I was full of nerves because I was there to perform at the Folger’s Elizabethan Theatre during one of their student festivals, and my mind was focussed more on remembering my lines than processing the exhibition displays that greeted us on entry.

Still, I remember stopping to take in the First Folio, seeing the famous Driscoll portrait of Shakespeare that is used in every literature textbook to signify the gravitas and importance of the literature it precedes. I couldn’t tell you now which of the Folios in the Folger’s collection I saw (they own 82), or which version of the Driscoll portrait I beheld (there are three), but I knew I was seeing something significant—so much so that I remember that moment more than I even remember how the performance went. Being in the Folio’s presence gave me chills.

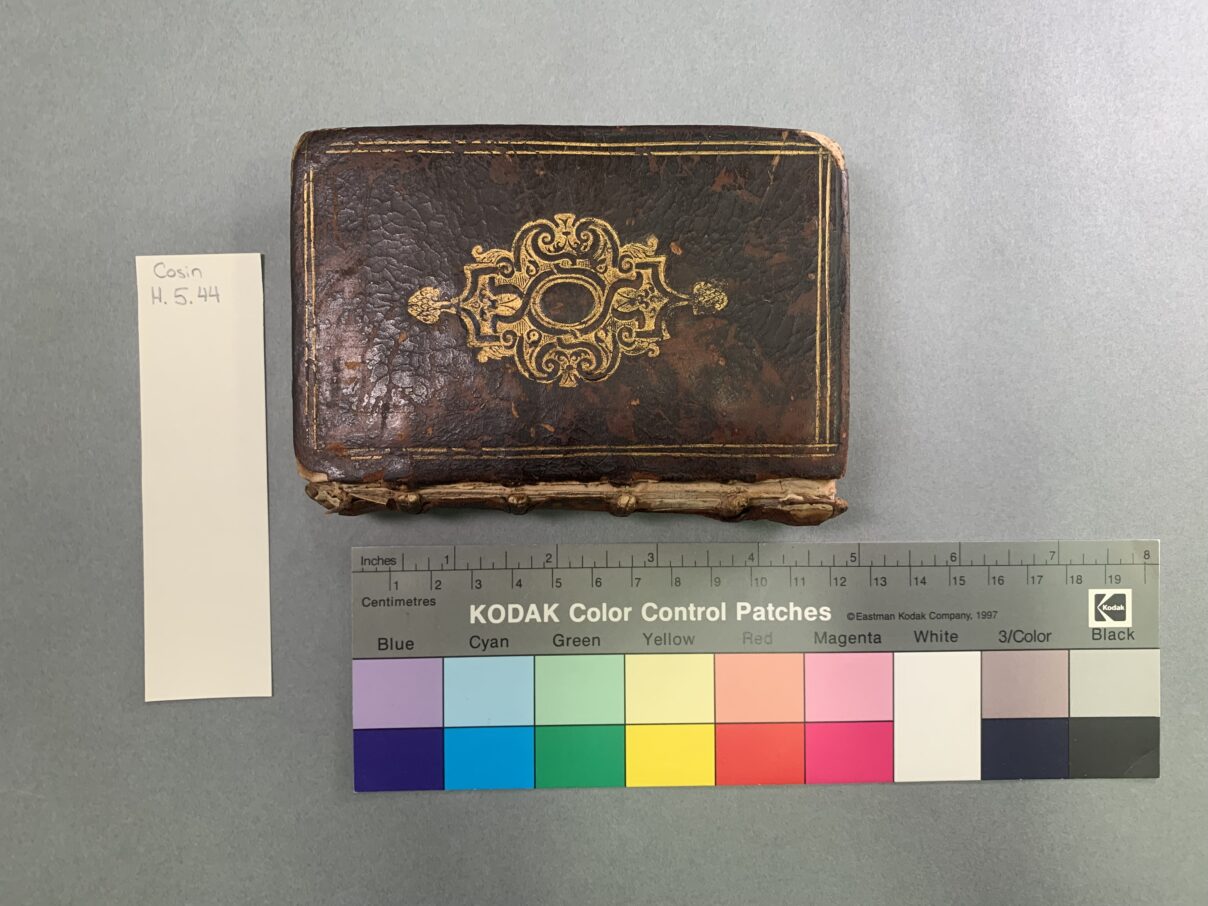

It’s been many years since the first time I saw a First Folio, and, having specialised in the conservation of rare books, I’ve had many encounters with them and their ilk since. In many ways, the Folio shouldn’t stand out in my mind. I’ve handled older and rarer books: on my bench at the moment is the only known copy of an edition of a book printed in 1576. Compared to the Folio, which was printed in 1623 and has 235 known remaining copies, the book on my bench is considerably older and rarer! Yet no great fanfare is made over its conservation; it’s simply one of the many books whose welfare I help steward.

So, what makes the First Folio so special? Why this book, when there are so many older and rarer to choose from? Is its reputation got without merit?

I say no! The Folio is special because it is so uniquely capable of giving an impressionable young teenager the chills. The Folio summons forth the magic of the stage, the pathos of great storytelling, the ethos of Shakespeare himself. It is at the same time quite a common book, and quite an extraordinary object that manifests an entire culture’s heritage in its venerable pages.

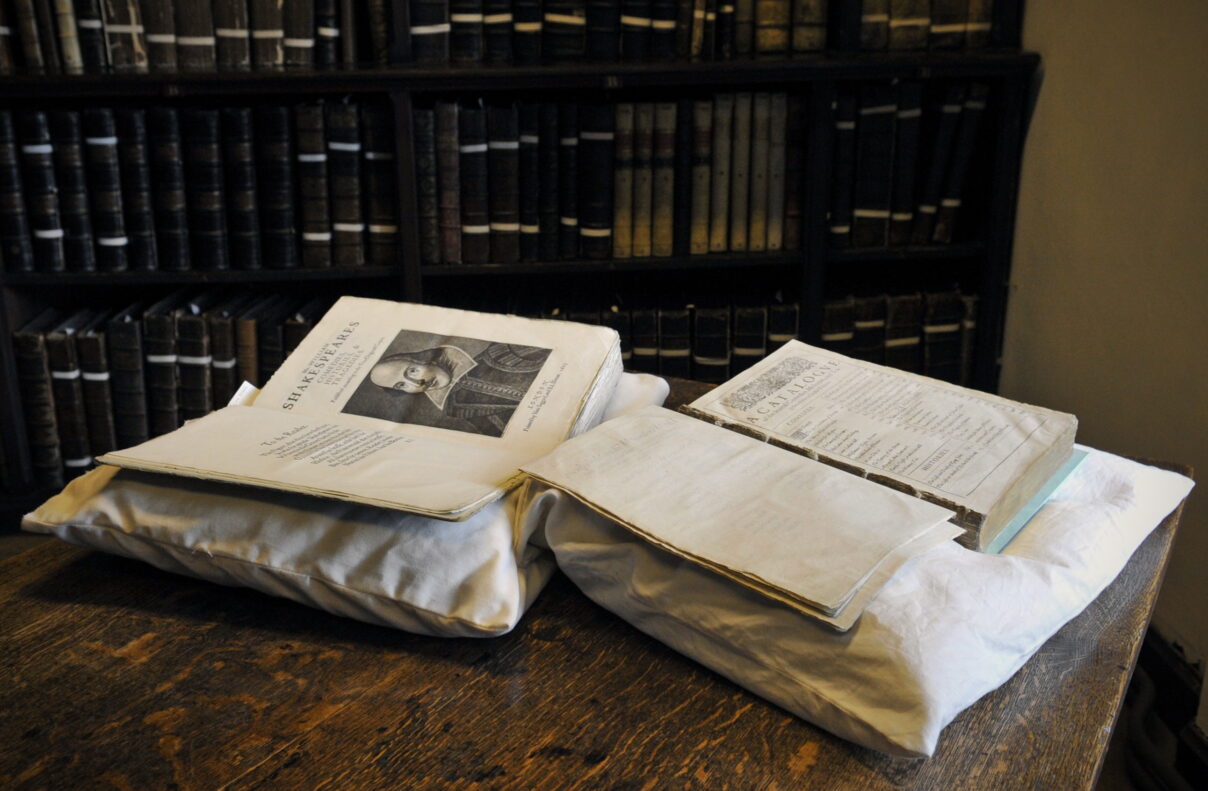

I, no longer an impressionable young teen, now work at Durham University, which is a proud owner of a First Folio. This Folio, sadly stolen and vandalised before its return to the University, is now in the care of my colleagues and myself, and it is our responsibility to steward its welfare going forward. We’ve been left with some very difficult decisions, and there are so many people who care about this book that we know no matter what we do, we’ll never manage to make everyone happy. So, I’d like to chronicle here the journey my colleagues and I have followed in the hope that you can see how and why we’ve chosen the course we have to secure a brighter future for this book.

And yes. I still get chills in its presence.